A Day of Excitement

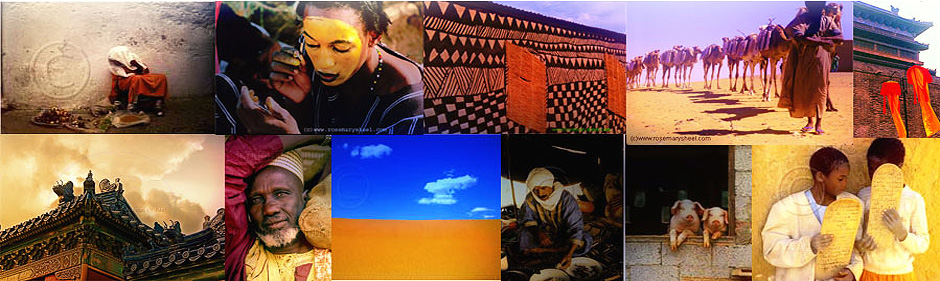

TransAfrica billed the adventure as the Ultimate Sahara Expedition: a 27 day extreme trek through one of the least explored regions of the Sahara.

Along with 6 other tourists, all of whom were Italian, we’d be making a circuitous crossing of 5000 kilometers of desert in 4×4’s. Our safari was to begin in Bamako, Mali then cross into Mauritania via the 6th century ruins of Kombe Saleh, stopping to visit the once important Islamic centers of Oualata and Chingetti. After Chingetti, the prospect of being alone in the desert for nearly five days loomed over us. Our lives would depend on the skills of our Moorish guide, Ali to show us the way back to Mali through the treacherous dunes of the Erg Chech. After weaving through the labyrinth of dunes, our route followed a northeasterly direction across ancient dry lakes to the salt mines of Traza which were abandoned 300 years ago. Eventually our small caravan would turn south toward the infamous salt mines of Taodenni and on to Timbuktu. Carrying our water, fuel and food as well as our own mechanics and armed guards, we’d be traveling through a part of the Sahara known only to bandits and smugglers.

My husband, John, and I had trepidations about the trip because we’d been robbed and left stranded by Kalashnikov carrying tribesmen on a previous trip to the Sahara. We know that a large part of the Sahara is lawless. No government can patrol limitless empty spaces; especially the cash strapped governments of West African countries where the police are lucky if they have a vehicle. Bandits and black marketeers who have the newest Toyota 4×4’s cross unmarked borders at will, roaming from Mauritania to Mali, Algeria, Libya and Niger.

But we had paid. We had our airline tickets. We were going. No looking back!

We arrived in Bamako close to midnight. The airport was a maelstrom of colorfully dressed men and women, gesticulating, laughing and yelling in French and who knows what tribal tongue. Young hustlers grabbed for our luggage assuring us that they had been sent to help us…Where was it now, that we wanted to go? We grabbed our luggage back and after a rather testy debate between John and me regarding the name of our hotel— Plaza or Park? We gripped our luggage firmly and waded into the sea of hustlers. Lo and behold, there in the writhing masses was a young man in a freshly pressed, white, cotton shirt holding a sign with our names.

Gratefully we entrusted ourselves to his care and we were soon lurching over the pot-holed, dark streets of nighttime Bamako toward our hotel, the Plaza. The night smelled of Africa. Heat and dust and woodsmoke and frying food and diesel exhaust and a murky river smell and then even more dust. The street vendors were still hanging in there trying to unload the last bananas or watermelons or loaves of French bread or bean cakes. Butane bottle lanterns glowing like fireflies lit up the shuffling throngs who were still, well, thronging. Always there is the sound of laughter. I remembered reading that the slave owners used to say of their black slaves, “But they are so happy!” Maybe even during slavery Africans could use laughter to make an unbearable existence bearable.

The next morning the fully loaded Toyotas were waiting in the hotel parking lot. Alberto Nicheli, our leader and the owner of TransAfrica, introduced us to our new companions. Although (except for one man) they said they didn’t speak much English, they knew more English than we knew Italian. Mostly in their late 40’s or early 50’s, they were a psychologist who worked for an Italian foreign aid program, a tour operator specializing in the Himalayas, a woman who seemed to be a professional traveler, as Mauritania would be the 201st country she had visited, and a retired executive. The others we would pick up the following week in Tjejeka, Mauritania.

We fell into a routine of driving 3 hours in the morning and 3 to 4 hours in the evening. Of course, time depended on how difficult the driving was. The worst was when the desert was filled with humps from sand collecting at the base of plants. The car we sat in was in need of new shocks. We learned quickly to sit lightly to avoid being catapulted into the roof as we churned through the obstacles. The car was owned by a Touareg man in Timbuktu, and using it was a form of insurance for us. Tribesmen on the lookout for easy prey would respect the property of a Touareg brother.

We made camp each evening as light began to fade and ate dinner under the stars. We rose at dawn and hurriedly dismantled our tents, packed our bags, dragged them to the cars and ate breakfast which was usually bread, jam and coffee. There was an Italian chocolate spread, but you’d have to fight the Italians for it, so we settled for peanut butter which they disdained.

The morning of our sixth day in the sahara began like all the other mornings. We ate breakfast, broke camp and took our places in the vehicles. I checked my camera for film and sighed. Another day of shooting landscapes. I wanted nomads. I wanted tents and camels. I wanted excitement.

The cars swooped like birds of prey over the desert as we tried to make good time toward Tichit which was 5 days distant. Sometimes the sand was hard and smooth. Then we flew along at 60 km/hr or more. Malian music, tinny and repetitious, blared from our driver’s cassette player. Osman sang under his breath in a high-pitched falsetto, his head nodding to the beat. The rocking, bouncing, swerving Toyota gyrated in sync under Osman’s delicate touch.

I stared out of the back seat window, lulled by the motion of the car, the landscape and the spectacular, blue skies filled with voluminous white clouds. On and on. Here and there small dunes with the ovoid shape of sea mammals broke the monotony of the endless horizon. Giovanni, who sat next to me, had his eyes closed as he told his prayers on his Buddhist beads. John’s head lolled in sleep. Only Osman, who seemed lost in his music, and I were witness to the passing desert.

By lunch time, the desert had changed into a rock strewn land with an occasional acacia tree. As I lurched stiff-legged from the car, I heard Alberto say that there was a beautiful view only ¾ km from our picnic site. He gestured to a dark cliff and announced that there would be time to explore during our stop.

Now normally, I am not interested in walking or hiking or trekking or whatever you want to call it. I’m a farmer girl and I’ve had my fill of nature. Give me a café in Venice, any day, I always say. Besides, I’ve noticed that you can only look at your feet and where you put them on these so-called hikes. If you breeze along looking at the trees or sky or whatever there is to look at, you’re liable to put your foot wrong and fall on your face.

So, it was odd that I decided to walk down to the cliff. Except that we’d been cooped up in the cars for several days and I wanted some exercise. No one else seemed to be interested in going so I set out by myself. I could see the cliff, though, and I figured I’d be back in 40 minutes at the latest. No Problemo!

Walking was easy; effortless. I was pleased that I felt so good. At my age, strength disappears quickly after a few days of inactivity. I remembered to carry my canteen. I carried my camera, as well. Even though it was high noon, there was always the possibility that I’d come across a good photo.

As I left, Alberto called to me to tell me that the cars would be parked under some nearby acacias to provide shade for our picnic. My little voice wanted to say, “But I won’t be able to see the cars if they are under the trees.” I didn’t listen to my little voice. Do I ever? It didn’t leave me though. Like a guardian angel, it sat on my shoulder and made me uneasy enough to note the direction of the sun and the angle of my shadow. I’d just reverse the two on my way back and I’d be ok. After all it was a straight line and I could see the cliff and it was only ¾ kilometer distant. No Problemo!

As I walked, I clambered over large, flat, orange-red rocks. Next to the rocks were coiled tracks in the sand from the snakes that lived under and between the rocky crevices. It was as if Medusa, herself, had lain next to the rocks leaving the outline of 30 or so writhing, twisting, slithering monsters. The sun was hot so the snakes had sought the shade, or so I told myself and I continued on. There was a vanity factor as well. I didn’t want to go back to camp and tell everyone that I hadn’t walked all the way.

After about 20 minutes, I reached the place Alberto had pointed out, but I couldn’t see the view without climbing over a wall of those snake infested rocks. I decided that I’d have better luck if I walked a bit more to the west, well, to my right, who knew west? After walking a few more minutes, I could see down into the valley, but here, too, was a wall of those rocks. By now, I was uneasy and wanted to get back to the camp. I could honestly say that I’d seen the danged cliff and it was beautiful and all that but I’d had enough. As soon as I started to retrace my steps, I realized that I’d been walking downhill the whole time. And now, I was walking uphill. And now, I noticed that I was a bit tired. I was carrying about 8 pounds of gear what with my camera, lenses (2) film, filters, and various necessities stowed in my photo vest. And so, I decided not to retrace my steps exactly. I’d angle toward my path.

Angling, that’s the key, I told myself. That way I’d save myself some walking. Of course, since I was angling, I couldn’t reverse the sun and my shadow the way I had so cleverly planned as I left the car. At least the sun and shadow were in a different place now. They were sort of the way I wanted them, though not exactly. However, as soon as I came upon my path and stopped angling, well, they’d be perfect! So, I angled. The sun seemed a lot hotter and after a while it came to me that I didn’t recognize anything. The undulating land was like a television re-run from hell. As I neared the top of the next shallow rise, I’d expect… hope… to see some landmark or other but no, everything looked exactly the same. Absolutely nothing was different.

The little voice was now a rather big voice. Having never been lost in my entire life, though, I had confidence that I’d find the camp. I imagined the relief I’d feel once I came upon camp and had flopped down to eat, laughing about my little ‘adventure’. More time passed and I hadn’t yet come across my path. And now I couldn’t get my shadow in the right place…the sun had changed. I looked back toward the cliff, thinking to use that as a marker, but even that had changed with the shifting light. And, Good God! There were two of those cliffs! I hadn’t noticed that before. Which one was ‘my’ cliff? I was still angling. Maybe I’d over-angled?? Was it time to do something else? I stopped angling and went into zigzagging, then spiraling, and everyone’s favorite, circles. I was like a demented figure skater.

My home is in Southern California and frequently there are stories on the news of people getting lost in the desert. I could hear the TV announcer’s somber voice intoning the warning: “Never go into the desert alone.” Well, too late for that one!! What’s next? “When you realize you are lost, stay in one place.”

How could I stay in one place? If I sat under an acacia tree, for sure, no one would find me. I’d be invisible under one of those trees. Now and then I would force myself to go under one, sort of touch base as it were. I’d take a sip of water and think. But what can I say? I’m a fast thinker and my thought was to get back to camp. So, I’d get up and go into my geometrics again, larger, smaller, east, west, who knew? I had to keep moving. How else would I find the camp? I scurried beetle-like from under trees, over rocks, through brush but never got anywhere.

Now the landscape was entirely different. It was filled with boulders. No vehicle could possibly drive here. Where was I? I veered in a new direction like one of those toy cars that hits the wall, bounces back and zooms off again. Now and then I’d climb to the top of what seemed like a big rock and scan the horizon with my telephoto lens. The rock was never high enough to see beyond the next undulation. I saw some camels but thought that the nomads might leave them out to graze for several days at a time. Somewhere in my farmer girl’s mind, though, was the idea that I could milk one of the cows if necessary. I decided to keep an eye on them.

I heard an unusual sound that sounded like a whistle but when I looked up I saw birds and thought that it was their cry I heard. And on I walked. 3 hours had passed. Now and then I’d get a gulpy feeling like I might cry, but what good would that do? It hit me about then that I was not going to find the camp. I looked at the empty, blue, sky that had seemed so beautiful a few hours ago and I knew that no helicopters would come roaring in to look for me. Someone had to find me, but how would that happen?

It was up to me to do something. I got the idea to make a flag from the white plastic bag that I used to protect my camera. I tied it to a branch from a dead tree. I held it aloft and it fluttered in the wind. Bright and white. If anyone was looking for me, they would see it. Then a gust of wind blew it from the branch and the white plastic bag skipped and tumbled into the desert. It was out of sight in seconds. I didn’t care that much. The branch was heavy and I didn’t really think that anyone would see me.

After that, I got the idea to pick up two stones and hit them together in a rhythmic sound. Sort of a substitute whistle. Clack. Clack. That got old in a hurry. I threw those down when I got the idea to start a fire. There was plenty of stuff to burn. If only I had matches or even some flint. I had neither.

I decided to use a filter from my camera as a magnifying glass. I piled up some dead leaves and grass and tried to shine the sun on it through the filter. It didn’t take me long to realize that a hundred years from now, they’d find my body hunched over those dead leaves with the filter in my hand and still no fire.

I screwed the filter back on the lens and stood up. Then I noticed a man in the distance. He was wearing a gandoura, the voluminous, indigo blue garment worn by Mauritanian men. Filled with relief, I hollered and waved my hands. He hollered back and we walked toward each other. I thought it might be the nomad who owned the camels I had seen, but it was Ali our guide. I could tell he was happy to find me. I could feel his heart beating as he gave me a hug. He had been afraid that I’d gotten injured.

I thought that since I had found Ali, I would be only a short distance from the cars but we were at least 2 miles away. (Technically, I did find him because I did see him before he saw me, after all.) I’d been walking for 3 ½ hours straight and I was tired but I forced myself to keep up with Ali’s long, swift stride. As we passed an acacia, Ali told me that I had stopped under that tree to drink some water. Huh? I had no idea I’d ever seen that tree before. Then Ali whistled to Hama, who was also tracking me, to let him know he’d found me and I recognized the ‘bird call’ I’d heard when I was lost.

Once Ali had determined that I was all right, he began to question me regarding the other woman in the group. She was my age, plump and on her way to getting plumper if her consumption of food was any indication. Moors and Touaregs are fond of plump women, even resorting to the forced feeding of honeyed milk to young marriageable females. Ali already had at least one wife, but Maria‘s mozzarella shaped figure had apparently stolen his heart.

The whole time I was lost, I had the comforting thought that John would be aware that I was missing and he would tell Alberto to look for me. John had gotten worried when I didn’t return after an hour. When he told Alberto, Alberto called to Ali and Hama, who were true men of the desert. “We’ll track her!” was their reply when he told them I was lost.

They began the search where I had descended from the car and were able to track me every step of the way. They were the ones who told me that I had gone in circles and zigzags. They were positive they would find me as long as I hadn’t fallen in a crevice. When they lost my trail because I had walked over boulders, they circled the rocks until they picked up my tracks again.

I felt ashamed and foolish because I’d caused so much trouble, but I think Ali and Hama actually enjoyed tracking me. It was much more suited to their talents than mollycoddling tourists. As for me, I was happy to lie down when we finally reached camp. I’d had enough excitement for one day.

Hi,

I read ur story and it’s nice.Is there any option to read these stories in other languages,i mean besides english.

Hi, Philip.

Glad you liked the story. It is only in English however.

Thanks for visiting my site.

Rosemary

Hi,Mary

Thanks for ur reply.But can i translate it in other language for u?Do u have any books about ur travel stories.Please let me know.

Hi Mary,

It is a nice story. I like storries from Sahara desert travels. Thanks..

Wow, this was so interesting!! I am so glad that they found you!! O_O

I’m glad you enjoyed reading that story. It was scary for me but I learned some things…Number one is do not go into the desert alone. I’ve got another scary story that your email makes me want to write. It’s about the time I was part of a group that was captured by bandits. That was scary, too!

Thanks for visiting my site.

Rosemary

awesome!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Hi, Kevin.

Thanks for your comment and for checking my site. I’ve just returned from Mongolia and will post some photos soon of Kazakh eagle hunters…check back in a few weeks.

Best regards, Rosemary