[nggallery id=8]

The castle at Fort Neemrana towers 500 feet above the dusty plain below. In the distance the Aravalli hills lie like a slumbering elephant. Sparse vegetation dots their boney surface like so many dusty hairs on its gray hide. A beseeching cry of “Krishna! Krishna! Krishnaaaaa!” floats to the sky from the pink temple in the village. Lime green parrots dart between their nest in the wall of the 14th century fort to the fuchsia Bougainvillea vines and the mango tree in the terrace garden. It is our last day in India and John, my husband, and I sit on our balcony that was once part of the zenana or harem and enjoy the view and our sweet lime sodas as memories of our holiday in Rajasthan come flooding back.

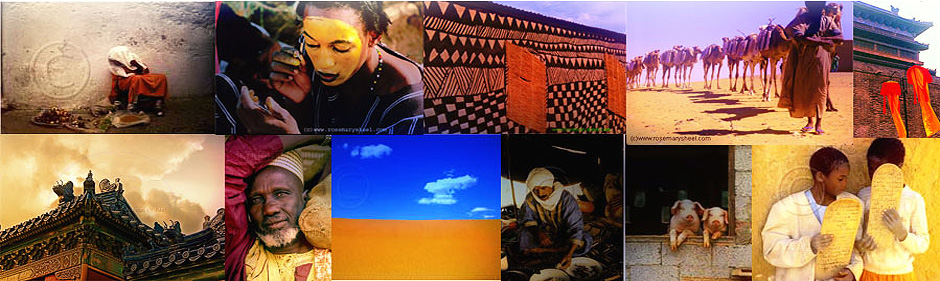

It was as if we had opened a treasure chest each morning and out had popped creatures and places as exotic as a fairy tale come to life. Majestic elephants stood calmly while tethered on the center divider of a main thoroughfare in Jaipur. Lordly, loose-limbed camels pulled carts and plows with a demeanor of smug superiority. Shopkeepers had to shoo clambering monkeys away from their doors before they could open for business and herds of a wild blue cow called Nilgi grazed complacently in fields of millet.

Holy men in orange shawls, their faces streaked with paint, roamed the roads and passed out marigolds as a form of prayer, but wanted money in return. Low caste women in jewel-colored saris balanced bowls of sand on their heads acting like human skip-loaders in a highway work gang yet keeping one eye on their soot covered babies who played happily in a pile of sand. A definitely not lower caste woman in a purple and gold sari reached out to paste a bindi on my forehead before jumping into her taxi.

We ambled through villages where ornate houses painted in magical colors of muted purples, lime green, sky blue and mustard yellow flanked narrow streets. We visited centuries old castles whose diwans or meeting rooms had once been cooled with indoor waterfalls and whose bedroom walls gleam sensuously with ruby colored mirrors. We climbed the walls of imposing forts such as Jaiselmer with its ninety-nine bastions that still stand guard over a dangerous frontier. We gazed with reverence at ornately carved thousand year old temples that shelter deities and bring solace to the faithful.

Our tour of India encompassed India’s Golden Triangle of Tourism (Delhi, Agra, Jaipur) but included Pushkar and Jaiselmer as well. Indian Moments Tours in Jaipur incorporated our suggestions of staying four days at the Pushkar Camel Fair, visiting the Taj Mahal and staying in palace hotels whenever possible. They arranged for our car and for our driver, Aksey, who stayed with us the entire trip. We became very fond of Aksey who subtly encouraged us to visit places we might have skipped. “A very good fort here. You are seeing?”

Three weeks earlier we had set out from Delhi for Agra and the Taj Mahal. Immediately we were plunged into the river of traffic that is known world-wide as India’s Grand Trunk Road. “Film this, John. No one will believe this traffic!” Seemingly half of India was driving south with us and the other half driving toward us, every horn sounding a bleating mantra. The famed truck transport of the Grand Trunk Road bowled toward us, causing John, who was sitting in the front seat, to stare out of the windshield with the look of a man whose life was passing before his eyes.

Caparisoned as if they were a prized camel, the truck windshields sported garlands of tinsel. Camel harness pom-poms tied to the side mirrors whipped in the wind. Hand painted flowers coiled across every spare inch of metal of the snub nosed orange colored Tata behemoths. Signs on the rear gate exhorted us to “sound horn for side” and “use dipper at night”. A wistful “no wief, no life” painted on the rear of one truck gave us some insight into the lonely life of a ‘truck-walla’.

It was a two lane highway but often we looked out to see three vehicles abreast, at least one of them aiming directly for us. At the last moment, the truck would veer sharply into the right lane, the overloaded carriage tilting precariously and we would catch a glimpse of dark, mustachioed men wearing bulbous turbans: kings of the road. Trucks, cars, motorized rickshaws, motorcycles with whole families on board, and bicycles carrying two or more neatly uniformed schoolboys packed the roadway. Along the side, going with the flow of traffic, a large Brahma bull strolled nonchalantly. At least he stayed in his lane.

We arrived safely at the Taj Mahal in late afternoon. The white marble minarets and domes glowed in the soft light against a hazy blue sky. Although the Taj was built as a tomb for Mumtaz Mahal, the beloved wife of Shah Jehan, it resonates with life and beauty much as the woman herself must have done. We joined the crowds gazing up at the Koranic prayers inscribed in graceful Arabic script around the main entrance and then entered the crypt to view the tombs and the marble walls inlaid with precious and semi-precious stones. The next morning we viewed the Taj from the Yamuna river side. Mist rose from the slow running water as a boatman poled us out to our vantage point. Bells and chants resonated across the water from morning prayers at the temple. A man and his bullock cart lumbered across the mud flats. For that moment we were a small part of ageless India.

The dust and heat of the Thar desert enveloped us as we arrived at Pushkar for the annual Camel Fair and the religious festival for Brahma. We were trundled to the fair ground in a camel cart from our tent city and trundled centuries into the past as well. Tribesmen, wearing curly toed shoes and dressed in white cotton dhotis with knee-length military shirts, camped with their camel herds waiting to sell or buy. Turbans of red, yellow, white, lime green and a plaid or two sprouted over the desert like tulips. To the camel herders who were squatting over campfires baking their chappatis (unleavened flat bread), smoking chillums (a cigar like pipe), or grooming, clipping and applying henna designs to sale animals, Pushkar fair is serious business.

Young boys playing sinuous sounds on sitars serenaded us as we wandered among the camels and the tribesmen. The tang of cooking chilis or chillys as the Indians spell it filled the air and drew us to the food stalls where daal (lentils) and chappatis were served on a recyclable bowl made of a molded leaf. After the diners were finished they cast their bowl aside and soon a cow ambled along to enjoy the leavings.

Wherever a crowd gathered we could be sure that a musician was in the center and if it was a big crowd more than likely there were dancing gypsy girls twirling and stamping in the dust. Veils flying, ankle bells jingling no one turned away until the dance ended. The girls were dressed in their best costume, heavily embroidered with mirror work. Their large gleaming eyes were rimmed with kohl and silver chains connected medallion-sized nose rings to ornate chandelier ear-rings. Although they had probably never been to school, they had a few words of English, “Nice pitcha, mista?” They accompanied this with dazzling smiles, swiveling their heads and fluttering their hands with the grace of a cobra.

We hired some camels for a ride to a nearby village where we took tea with one of the village men. Being of Rajput caste, the women were kept in purdah and not allowed to meet John. Yet they called hello and peered over the wall to look at us while taking care to keep their faces covered. Our camel guide told us that when he marries, his wife will not be allowed to speak to him in his mother’s presence, nor will he be allowed to speak or even look at her while his mother is in the room. What transpires when his mother leaves the room is left to the imagination!

Our home in Pushkar was the Royal Desert Camp where rows and rows of white and blue Swiss Cottage tents were set up in the dunes. Gomer Pyle would have felt right at home except our tent had a little screened in porch and complete bathroom facilities. Like Gomer, we ate in the dining hall and since it was Diwali, an especially holy time at Pushkar, our menu was ‘pure veg’. That meant no meat or eggs just plenty of eggplant, cauliflower, lentils, rice, cabbage and lady’s fingers (okra) all heavily laced with fiery hot pepper. We took to dousing everything with yogurt. Later, after several groups of English and Germans joined us, someone must have taken the cook’s pepper can from him, because the food became considerably more palatable to us.

The palace at Deogarh was just what we needed after tent life in Pushkar. Resembling a French pastry, the cinnamon and white colored home of the Sangawat clan, looms over the village on the only high ground of a wide plain. We were shown to the Peacock room that was formerly a part of the harem. Tiny colored windows looked out on the castle entrance allowing the secluded women to keep track of visitors to the court. Lovely frescoes hundreds of years old showing scenes of elephant hunts and sweet faced Brahma cattle depict life as it used to be.

As we were eating our lunch in the upstairs piazza, a dignified woman wearing a sari stopped to ask us if we were enjoying ourselves. When I asked if we were staying in her home, she answered, “Yes.” She was the mother of the present Maharaja and she sat with us for a few minutes as we discussed a bit of the history of purdah in Rajasthan. Later, the Maharaja, himself, invited us to watch a video he had just made observing a leopard teaching her cubs to hunt.

Although I prefer to concentrate on photography when traveling, it was in Jaipur that I succumbed to shopping fever. It wasn’t that we actually bought anything in Jaipur. It was that our guide introduced us to the plethora of reasonably priced, well made goods that India and Jaipur in particular had to offer. He began with carpets, segued to block printed table linens, miniature paintings and last the jewelry made of the precious and semi-precious stones that Jaipur is famous for. When we didn’t buy, he was as disappointed as only a man who has watched his big fish get away could be.

Little did he know that he was smoothing the way for other guides in future cities. He would be gnashing his teeth if he knew how many dollars we would hand over in Jodhpur and Jaiselmer as we scooped up silk saris, embroidered cotton bedspreads, block printed table linens, hand forged table ware, wall hangings made of antique sari scraps embroidered with silver and the miniature paintings that John began to collect.

Call me crazy but I wanted a dhoti. I admit the sari is perhaps the most beautiful and flattering garment a woman can wear, but I wanted to know how a dhoti works. How is it possible to make an attractive pair of trousers from a tablecloth by tying only one knot? I asked several men to tell me how it was done. The question seemed to embarrass them. Although an older, rather sophisticated, man tried to tell me how to hold ’em and how to fold ’em using words and gestures, I had the feeling that he had forgotten a strategic maneuver.

It was in the tiny village of Narlai, where we stayed in a 500 year old hunting lodge, that I found the local shepherds wearing the most beautiful dhotis I had seen. The fabric was white, embroidered with bright reds and greens and I was determined to buy one. Even if I couldn’t wear it, I could always drape it over a piece of furniture. I asked one of the lodge’s porters to help me to buy a dhoti like the one he wore. Bogwan (it sounded like that to me) agreed and off we set through the village dirt lanes. The shop owner was entertaining his friends with a cup of chai when we entered and Bogwan, who was as shy as a leprechaun, if you can imagine a tall, bamboo-thin leprechaun, relayed my request.

Black eyes opened wide and stared at me in shock. “Dhoti” “Me” I pointed to my chest. A hissing exchange of words with Bogwan before the dhotis were reluctantly drawn from the shelf.

Ah! It was exactly what I wanted. “Yes, and a kurta” (tunic). More consternation. “But, madam! These are men’s clothes!” wailed the shopkeeper.

I wasn’t listening. I held out my unfolded dhoti. “How do I put it on?” No one moved. I could see none of the men was willing to show me because it would involve touching me. They decided that Bogwan would have to do the deed. Though I don’t know a word of Hindi, I could understand. “You were the one who brought her here, you show her.” And he did, holding the cloth around me, tying one end to fit around my waist and pulling the corner through my legs (I helped here.) to tuck in the waist at the back. Suddenly, I was resplendent in white poufy Capri length pants. I loved it even with my dusty khakis showing underneath. Then the kurta. It was much too small through the shoulders but I bought it anyway. I’ll put it in the closet with my Romanian sheepskin coat, my Grand Boubou from Niger, and my Moroccan djellaba.

Hi Mary I’m an Indian and I myself think that you should go to the Golden Temple in Amritsar!!!

Hi, Steve.

I’ve seen photos of the Golden Temple in Amritsar and I agree. It is a beautiful place and inspiring as well. Next time I go to India…if I do go again…I’ll put it on the top of my itinerary.

Thanks for visiting my site and for taking the time to email. I appreciate it.

Rosemary

Just reread this. Exquisite imagery! Makes me want to go back and I only just got home. But your magical Rajasthan is hard to find these days. How lucky to have seen it then and thank you for documenting and sharing it so poetically and beautifully!

Dear Torie,

I appreciate praise no matter who offers it but when a writer of your caliber writes such kind and generous words, I am truly honored.

Rosemary